Organic Phenomena

Organic Phenomena

Brett Wood unearths

DAVID LYNCH's Deepening Mysteries

By Brett Wood

film historian in College Park, Georgia

Art Papers (FOCUS ON ART AND FILM), 22/5 Sept.Oct 1998

As a filmmaker, David Lynch has established his place in the forefront of contemporary cinema, intrepidly following the path of his dark and sometimes strangely comic imagination, even on its course into psychologically deep, dauntingly uncommercial and critically treacherous waters.

Lynch's keen visual aesthetic varies between vibrant, spacious Edward Hopper-influenced compositions and biliously claustrophobic sequences that suggest a reality only one step removed from nightmare. Lynch's talent lies in keeping the viewer ankle-deep in ever-shifting psychological and aesthetic sands, orchestrating eerie convergences of opposite extremes, in a surreal landscape where absolute meaning is never clear. The coalescence of rusted metal and white picket fences, of adult corruption and youthful innocence, of deception and truth, of explicit meaning and baffling metaphor have made Lynch perhaps the most noteworthy filmmaker working in a decade characterized by tired self-referentiality, empty post-mod homages and too many mavericks gone mainstream.

These same qualities which distinguish his films apply to Lynch's artwork as well, and have earned him renown as a painter and photographer, with solo exhibitions at New York's Leo Castelli Gallery, Los Angeles' James Corcoran Gallery, Tokyo's Museum of Contemporary Art, Paris' Galerie Piltzer and the Sala Parpallo of Valencia, to name a few.

In recent months, Lynch, who in his pre-filmmaking years studied painting at Boston's School of the Museum of Fine Arts and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, has turned his creative focus to printmaking after accepting an invitation by the Tandem Press to be a visiting artist. "David Lynch came and visited the press and expressed his interest in making prints," says Tandem curator Tim Rooney, "and we set the dates and shortly thereafter went into production." Limited editions of these new works (which have shown in Chicago, St. Louis, Santa Fe, Dallas and Indianapolis) are being represented by Tandem Press, a self-supporting studio which operates under the auspices of the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Education.

"The simplicity and the mystery of Lynch's prints appeals to me," says Rooney, "The basic iconography of the works attracts the viewer and the text adds an element of mystery beyond the initial impact of the imagery."

In certain regards a departure in style and process from his previous work, the recent prints nevertheless continue many of the themes and images that haunt his earlier compositions. Heeding the visual and psychological compulsions that beckon the artist's imagination, these more recent works shed some of the awkward quirkiness that sometimes diminished the impact of his previous creations.

A dominant work among Lynch's recent prints-both in size and in beguiling power-is The Eight Quarters (1998), a nonrepresentational, four by eight foot composition which is presented in a varied edition of 20. Like the mesmerizing lyrics Lynch composed for Julee Cruise and the perplexing phrases scattered throughout the film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992), the text, neatly engraved in rows across the ink-washed surface of the paper, offers a beautiful but ultimately indecipherable message to the viewer ("the eight quarters were resounding with noise and there was darkness everywhere").

From his earliest known work, text has been an integral visual ingredient for Lynch. His first short film, Six Men Getting Sick (1967, which Lynch refers to as "more of a moving painting than a film"1) opens with a numerical representation of each figure, and his second film, The Alphabet (1968), features an animated sequence in which a mutant garden is formed of blossoming, bursting, bleeding letters. Lynch's oil on canvas and ink on paper paintings generally included bits of tormented free-association-writ in quivering hand like the scrawl on the wall of Sybil's closet, or else tiny letters scissored from newsprint (like the "R" under Laura Palmer's fingernail) and pressed onto the canvas' congealed surface.

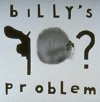

In these recent prints, the once oblique captions have evolved into cleaner, bolder lettering which should, judging by its commanding scale, pronounce absolute meaning upon the compositions. Instead, this authoritative wordage is just as cryptic as the minute messages integrated into Lynch's previous paintings. An untitled print, captioned "billy's problem" (1997, one in a series of 41 monoprints), sandwiches between its overbearing words the rough silhouette of a handgun, a blocky question mark and, at the center, an amorphous grey stain which foils all efforts at interpretation. This significant void-which could represent an unfocused alternative to the gun or might represent the ill-defined "Billy" himself-recalls the blue rose, the Black Lodge, the Lumberton drug scam, the plight of Fred Madison and all the other impenetrable Lynchian mysteries that, like dreams evaporated upon waking, defy clear understanding and tidy resolution and thereby haunt the spectator long after the image has faded from view. The "Billy" prints continue Lynch's treatment of the blind fear and confusion suffered by childlike figures. In a less vaguely diagramed rendition of "billy's problem," another print depicts a somewhat-human head with the gun aimed definitively at its temple.

In these recent prints, the once oblique captions have evolved into cleaner, bolder lettering which should, judging by its commanding scale, pronounce absolute meaning upon the compositions. Instead, this authoritative wordage is just as cryptic as the minute messages integrated into Lynch's previous paintings. An untitled print, captioned "billy's problem" (1997, one in a series of 41 monoprints), sandwiches between its overbearing words the rough silhouette of a handgun, a blocky question mark and, at the center, an amorphous grey stain which foils all efforts at interpretation. This significant void-which could represent an unfocused alternative to the gun or might represent the ill-defined "Billy" himself-recalls the blue rose, the Black Lodge, the Lumberton drug scam, the plight of Fred Madison and all the other impenetrable Lynchian mysteries that, like dreams evaporated upon waking, defy clear understanding and tidy resolution and thereby haunt the spectator long after the image has faded from view. The "Billy" prints continue Lynch's treatment of the blind fear and confusion suffered by childlike figures. In a less vaguely diagramed rendition of "billy's problem," another print depicts a somewhat-human head with the gun aimed definitively at its temple.

With his round hollow skull atop a slender stem of a body, Billy in the past was the subject of Billy Was Halfway Between His House and the Sickening Garden of Letters (1990) and Billy Finds a Book of Riddles Right in His Own Back Yard (1992), which distill the themes of textual conundra and organic mystery so elemental to Lynch's work. Ricky Fly Board (1997, a collage with flies and india ink on paper) is a revisitation of the "Ricky Boards" and "Bee Boards" pictured in Lynch's 1994 book titled Images and which were played for laughs during the artist's appearance on The Tonight Show. Gone are the tiny labels that once identified each mounted bee (e.g. "Dougie," "Dave," "Ed," "Chuck") and drove the work into the territory of camp, the kind of whimsical flourish that tended to perpetuate the image of Lynch as a "Jimmy Stewart from Mars" and inspire the New York Post to dub him, "A Real Quirkmeister." This revised Ricky Fly Board conveys far more by saying much less. The mathematically precise yet unexplained arrangement of insects on a white field glows with the suggestion of hieroglyphic scientific activity-its meditation on symbolic meaning underscored by the artist's signature as "(thumbprint) = D.L."-and is closer in form to the clinically morbid work of artist Damien Hirst than the tongue-in-cheek creation of a cornpone hobbyist. Ricky Fly Board is a welcome departure from the off-beat persona which Lynch was often content to hide behind and, along with the other prints in this collection, calls for a more serious consideration of his status as a true multi-media artist.

In a similar revisitation of a previous work, Lynch took the painting captioned Ant Bee Mine (1992), which might have been dismissed as a valentine from one Mayberry bug to another, and re-envisioned it as Ant Bee Tarantula (1998), in which a disembodied head floats, vomiting, against a sea of grey that recalls the horizontally-streaked backgrounds of his earlier, similarly monochromatic paintings. Like the confused but deeply significant etchings of a psychologically troubled child, Ant Bee Tarantula resembles the "Billy" series and Lynch's earlier paintings which indulge a juvenile perspective to wrestle with the moods and mysteries of nightmare and the subconscious, the potent effects of which defy conscious and adult understanding.

The explicit references to menacing insects (which, significantly, are not visually evident) brings to the forefront another potent symbol in Lynch's work. His father, a research scientist for the Department of Agriculture, often experimented with tree diseases and insects, and this exposure to decay formed memories that Lynch has frequently harvested. "There's a lot of slaughter and death, diseases, worms, grubs, ants," Lynch later recalled, "On the cherry tree there's this pitch oozing out-some black, some yellow, and millions of red ants crawling all over it. I discovered that if one looks a little closer at this beautiful world, there are always red ants underneath."2

In much of Lynch's work, insects undermine the balance of society, evidenced in the beetles that churn beneath the manicured turf of Lumberton and the gargantuan insect that fills a domicile with its segmented body and a wet grey stain in a print captioned "ant in house." The resonant earlier painting Shadow of a Twisted Hand Across My House (1988) posits a huge claw against an institutional-looking dwelling while a truck-sized grasshopper sits idly watching from across the canvas. A similar expression of a child's-eye paranoia of insects and adulthood (an apt description of many of Lynch's paintings of the 1988-93 period) is found in Bugs Are in Every Room-Are You My Friend? (1992). In a recent blending of art and parasites, Meat as a Face With a Bird and a Rat (1997), Lynch made a raw steak the centerpiece of a painting (flanked by two small carcasses), then allowed assorted insects to erode a good part of the meat before shellacking it in the desired state of decay.

Hand in hand with organic decay is the industrial erosion that surfaces in much of Lynch's work, such as the grisly tangle of Band Aids and sludge that constitute Garden in the City of Industry, a 1990 painting. The clash of natural and industrial is treated with zenlike clarity in the print "rain," in which an opaque cloud of tar drips thick black slugs across a blurred sun.

Appealing on one level to his sensory fondness for rust, soot and grime, it also expresses a horror of apocalyptic social decay perhaps best represented by Lynch's former home of Philadelphia. Many of Lynch's most troubling memories originated while living in a high-crime area of the city, which he has called, "the most violent, run-down, sick, decadent, dirty and dark city in America. To go there is like entering an ocean of fear."3

Inspired by an image from Lynch's astounding, untitled 50-second film made in commemoration of the Lumiere Centennial, Woman in Tank (1997) is a hypnotic composition that shares the bleak aesthetic of his "Industrial Photographs" series while echoing the artist's laboratorial curiosity hinted at by Ricky Fly Board. Within layers of grey murk (as if the entire scene were under fetid water upon the floor of "an ocean of fear"), the figure of a woman is revealed trapped inside an enormous glass vat fed by a hose and suspended from a series of steel cables. The tableau succinctly voices the blend of horror and fascination that Lynch has for years evinced toward medical science and the freakshow (and the grisly attributes they share). A man alongside the tank, gripping its controlling levers, might be a scientist, a carnival spieler or both-a modern-day rendition of the 18th century mountebank who, with his mystical pseudo-scientific lectures and jars of contorted flesh, instilled awe and instigated nightmares in the minds of the peasantry that wandered curiously past his traveling stage.

The exhibition of the Elephant Man (by doctor and showman alike) and the shriveled specimens that float forgotten in glass jars on dusty shelves in Lynch's "Organic Phenomena" photographs suggest evidence of science's shameful failings rather than trophies of progress. In a photograph taken within an operating theatre now unsanitary with grime and tainted by darkness, an enormous lamp mounted above a dissection slab stares into Lynch's lens with a gaping black void, an empty eyesocket no longer possessing the power to illuminate.

Among the 41 untitled monoprints are a series of portraits of gnarled and pitted faces that, more than any of his previous work, reflect the indelible impact Francis Bacon (specifically his disfigured portraiture of the 1960s and '70s) had upon Lynch's fine art. "I saw Bacon's show in the '60s at the Marlborough Gallery," Lynch said in a 1997 interview, "and it was really one of the most powerful things I ever saw in my life."4 The primary difference between the two groups of portraits is that Lynch avoids the realistic facial features and clean lines that tend to show through the twisted and blurred surfaces of Bacon's headshots, favoring instead faces so misshapen that they are only vaguely human. The identical black-suited shoulders at the base of each composition are necessary signifiers that the bulbous shapes above are actually human, leading one to recognize the hollow craters as mouths, nostrils and eyes. At the same time, the suits convey the Lynchian duality by pairing formal attire with grotesque visages that alternately resembles smashed animal skulls and elephantine wads of dung and pitch.

The fragility of the flesh, the malleability of the organic, is expressed in the masses of gum and gobs of paint that often represent the human form in Lynch's artwork and is a primary element of the Bacon-inspired Six Men Getting Sick, whose stomachs fill with blood and spill their contents just before the heads themselves release bile down the length of the frame. The head in the 1997 print captioned "red cloud" repeats this final action, though the crimson stain is more gaseous than liquid, recalling the erotic vapors that seep through rouged lips in Lynch's series of "Nudes and Smoke" photographs.

In the rich, dark paintings of his past, Lynch's humans assume an embryonic form, with skull-like bulbous heads, gaping lipless mouths, hollow eyesockets and bodies that taper into long snakelike legs (not unlike the multiple miscarriages of Eraserhead, 1976).

The fragility of the flesh, the malleability of the organic, is expressed in the masses of gum and gobs of paint that often represent the human form in Lynch's artwork and is a primary element of the Bacon-inspired Six Men Getting Sick, whose stomachs fill with blood and spill their contents just before the heads themselves release bile down the length of the frame. The head in the 1997 print captioned "red cloud" repeats this final action, though the crimson stain is more gaseous than liquid, recalling the erotic vapors that seep through rouged lips in Lynch's series of "Nudes and Smoke" photographs.

In the rich, dark paintings of his past, Lynch's humans assume an embryonic form, with skull-like bulbous heads, gaping lipless mouths, hollow eyesockets and bodies that taper into long snakelike legs (not unlike the multiple miscarriages of Eraserhead, 1976).

In a 1988 series of photographs (e.g., Man With Instrument, Man Thinking), the head of a toy policeman's body has been replaced with a swollen knot of chewing gum, devoid of human facial features, streaked with creases like one enormous furrowed brow-an emphasis on mutation and the abject similar in vein to the work of artists Cindy Sherman, the Chapman brothers and Paul McCarthy's grotesque unions of kitsch and the macabre. Photographs of melting snowmen taken by Lynch in his boyhood home of Boise, Idaho express this same curious and dreadful phenomenon, as does a sculptural experiment in which Lynch moulded clay around a ball of turkey and cheese and fashioned it into the shape of a head, then watched as his favored ants entered the mouth and eyes and steadily devoured the head from within.

As these works attest, the head is an anatomical portion upon which Lynch concentrates the most energy, as it is the repository of consciousness, in all its wonder and horror, and the part most sensitive to damage-vividly expressed in "red cloud" and a print in which a head radiates surprise as a bullet passes through it. Head trauma abounds in his filmic work: fatal gunshots or blows to the head claim victims in Dune (1984), Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks (1989), Wild at Heart (1990), Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me and Lost Highway (1997), while Eraserhead and Wild at Heart feature full-blown decapitations. In nonviolent situations, Lynch routinely distorts heads by lens (Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart and Lost Highway) and by makeup (Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, 1980), indulging his obsession with facial disfigurement as a visual representation of interior anguish.

Many of the pieces in the monoprint series eschew the shoulders in their representation of disembodied heads. But in these prints, the heads are identified as such by more recognizably human features and, in some cases, large block letters spelling, simply, "head." Like uniform masks frozen in expressions of intense anguish, these more identifiable faces stare forward with eyes and mouths agape, sometimes paired with the same ambiguous ink stains that helped convolute "billy's problem." The grey oval stains serve as shadows to the floating heads, and in some cases eclipse other forms that lie obscured beneath, again presenting mystery without resolution.

The smooth texture of Lynch's prints sharply contrasts with the gooey mire of his canvases, upon which are mounded oil paints, housepaints, roofing tar and such found objects as Band-Aids, dead animals and even cuts of beef. Inspired by the action painters of the late 1940s and '50s, as well as such nonrepresentational artists as Mark Rothko, Lynch habitually paints by smearing, mixing and sculpting globs of paint until they (typically but not always) assume vaguely identifiable forms. "I hate slick and pretty things," Lynch told Buzz Magazine in 1993, "I prefer mistakes and accidents. Which is why I like things like cuts and bruises-they're like little flowers."

In this recent series of prints, Lynch has expanded the breadth of his vision to yet another medium with great proficiency and achieved a level of artistic maturity exceeding that of his previous work. The white backgrounds and often simple designs of his prints reflect a tendency toward a cleaner aesthetic, though he has sacrificed none of the darkness and grotesquerie that have for years characterized his work in various media. Even the furniture that Lynch has been designing recently-which more closely resembles postmodern Italian works than the earthy, organic constructions one might expect-might be described as grotesque for its asymmetrical and strangely disproportionate design.

One hopes that Lynch will continue to cultivate this facet of his work along with the higher-profile cinematic endeavors for which, at least for the present, he will continue to be known.

Notes: 1. Pretty As a Picture, 1997. Video documentary by Lynch's longtime friend Toby Keeler, whose father, Bushnell Keeler, inspired Lynch to pursue a career as an artist. 2. Rodley, Chris (ed.), Lynch on Lynch (London: Faber and Faber, 1997), pp. 10-11. 3. Cinephage, no. 6 (May-June 1992). 4. Rodley, Lynch on Lynch, p. 16. Lynch is probably referring to the 1968 show at New York's Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, though it could also be the 1963 Marlborough Fine Art Gallery (London) or the 1967 Marlborough Galleria d'Arte (Rome), all of which hosted solo shows of Bacon's work.

Brett Wood is a film historian in College Park, Georgia. He recently edited Mayhem, Motherhood & Madness: Three Screenplays from the Exploitation Cinema of Dwain Esper (Scarecrow Press).

Prints | Paintings & Drawings | Photographs | IMAGES | David Lynch main page

© Mike Hartmann

thecityofabsurdity@yahoo.com

photos by Jim Wildeman, courtesy of Tandem Press